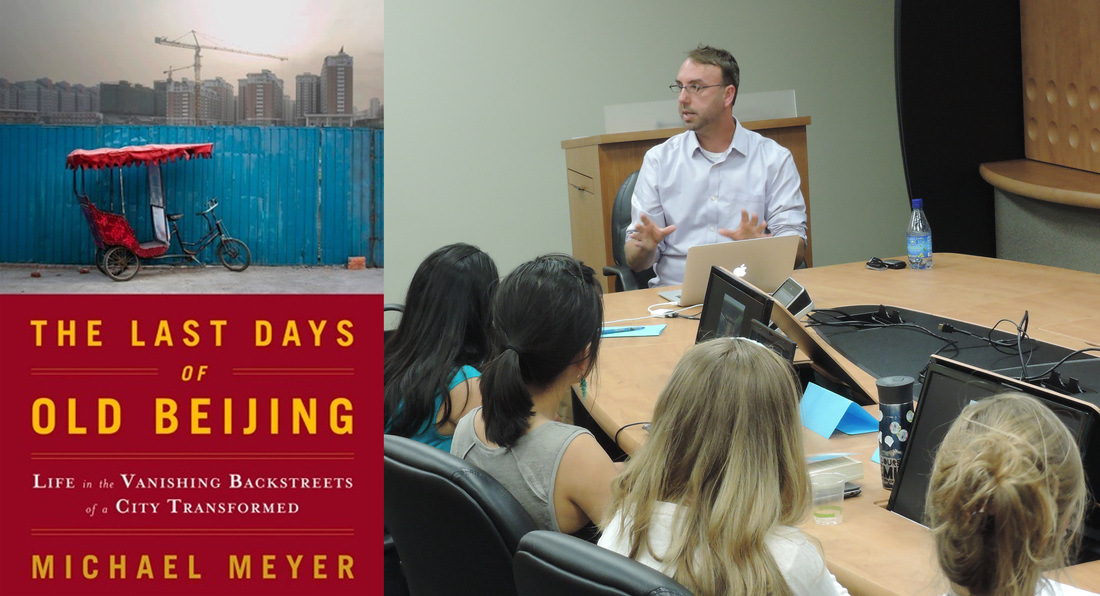

This evening, the award-winning author Michael Meyer spoke to a joint session of students in URBANST145 (based at Stanford) and URBANST102 (based in Beijing). He made clear that he does not take a "sentimental" approach when studying communities; yet his clear-eyed analysis still yielded the sense that it is meaningful to save the hutong and its vibrant style of living.

The conversation was wide-ranging, with students chiming in from both sides of the Pacific. Some of the other key points we discussed included:

(1) The growing importance of traditional culture to Chinese citizens, who are beginning to recognize that it is part of their identity. This includes young people, to whom saving the hutong is a worthy cause, as well as the residents of the hutongs themselves.

(2) Decisions to demolish a neighborhood or to encourage its preservation often come from elite-led movements, but when discussing the future of a neighborhood, what about the people who live there now? It seems appropriate to bring the voices of current residents into planning discussions as well. There is an ethical basis to this, as it is right to include people to understand their needs and aspirations and seek their consent. There is a practical reason to do so: solutions are more likely to be well-received and effective in the long run if we first engage the grassroots.

To date, urban redevelopment has been driven by priorities of real estate developers, business leaders and local government officials. Conservation-minded outsiders have been able to chime in on some projects. But it would be meaningful to ask the silent constituency of people who currently live in the neighborhood about their needs, wants, and hopes for the future, to determine how we structure our communities.

(3) The rapid pace of development in China means that society may not have the opportunity to discuss social issues and make choices with deliberation. Changes are happening so quickly that communities, buildings and architectural features, and entire ways of living might be erased before there is a chance to establish a social consensus on how best to pursue modernity, while still preserving what matters. That's why it is important to make an effort now while possibilities still exist.

(4) However, these urban development issues do not pertain to China alone. Cities in the United States and elsewhere around the world also face hard questions of change and evolution, whether it is how to deal with the impacts of gentrification, to more fundamental questions concerning "the kind of community we want to be." According to Meyer, after a spate of shocking incidents, the city of Santa Cruz (where he resides for part of the year), is now considering whether to establish a municipal police force after many years of living without such an institution.

Overall, the comparative lens has proven to be an insightful one, as the changes in China are put into a global context. Meanwhile, lessons from the Chinese situation can be applied in our home countries.

The conversation was wide-ranging, with students chiming in from both sides of the Pacific. Some of the other key points we discussed included:

(1) The growing importance of traditional culture to Chinese citizens, who are beginning to recognize that it is part of their identity. This includes young people, to whom saving the hutong is a worthy cause, as well as the residents of the hutongs themselves.

(2) Decisions to demolish a neighborhood or to encourage its preservation often come from elite-led movements, but when discussing the future of a neighborhood, what about the people who live there now? It seems appropriate to bring the voices of current residents into planning discussions as well. There is an ethical basis to this, as it is right to include people to understand their needs and aspirations and seek their consent. There is a practical reason to do so: solutions are more likely to be well-received and effective in the long run if we first engage the grassroots.

To date, urban redevelopment has been driven by priorities of real estate developers, business leaders and local government officials. Conservation-minded outsiders have been able to chime in on some projects. But it would be meaningful to ask the silent constituency of people who currently live in the neighborhood about their needs, wants, and hopes for the future, to determine how we structure our communities.

(3) The rapid pace of development in China means that society may not have the opportunity to discuss social issues and make choices with deliberation. Changes are happening so quickly that communities, buildings and architectural features, and entire ways of living might be erased before there is a chance to establish a social consensus on how best to pursue modernity, while still preserving what matters. That's why it is important to make an effort now while possibilities still exist.

(4) However, these urban development issues do not pertain to China alone. Cities in the United States and elsewhere around the world also face hard questions of change and evolution, whether it is how to deal with the impacts of gentrification, to more fundamental questions concerning "the kind of community we want to be." According to Meyer, after a spate of shocking incidents, the city of Santa Cruz (where he resides for part of the year), is now considering whether to establish a municipal police force after many years of living without such an institution.

Overall, the comparative lens has proven to be an insightful one, as the changes in China are put into a global context. Meanwhile, lessons from the Chinese situation can be applied in our home countries.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed